Twenty years ago, I met Hayao Miyazaki for the first time. Princess Mononoke was his first film to receive a major US release, and my editors at the LA Times let me do a profile of him.

We met at a hotel in West Hollywood; we sat at a garden table where he was free to smoke. I didn’t speak any Japanese, nor did Miyazaki speak any English. He struck me as an intense man, who thought carefully before replying to my questions. Since then, I’ve done other interviews with him, introduced programs with him, and visited him at Studio Ghibli. My respect for him as an artist and filmmaker has only grown.

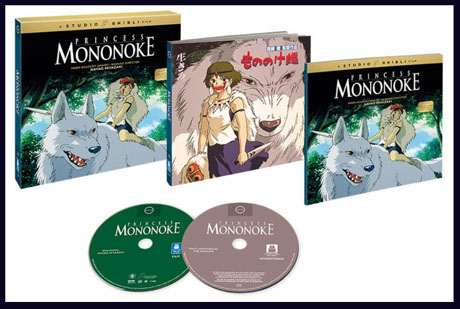

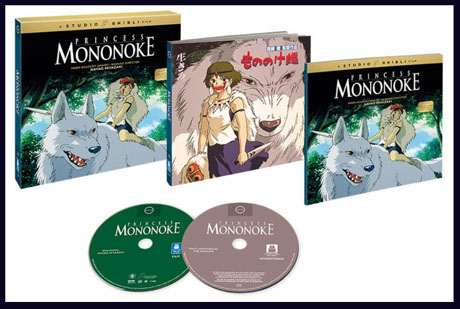

To mark the 20th anniversary of its US release, Gkids has issued a new Blu-ray of Princess Mononoke and a disc of Joe Hisaishi’s score, packed in thick cardboard pages that suggest a children’s book. It also comes with a pamphlet that includes Miyazaki’s poems about the characters (which were printed in “The Art of Princess Mononoke”) and an essay by Glenn Kenny. Among the extras on the disc—which have been included in earlier editions—is the Japanese documentary Princess Mononoke in USA, which I’d never watched. Although I remember a Japanese crew filming while we talked, I was surprised to hear my voice asking Miyazaki about the film’s ending and to see him signing my copy of the “Art of” book, which I still have.

Twenty years later, Miyazaki’s comments seems as powerful and thought-provoking as they did then, so Jerry agreed to present the interview I did two decades ago.

At the Head of the Pack

By CHARLES SOLOMON

Oct. 24, 1999

Director Hayao Miyazaki makes his animated features primarily for Japanese audiences. Yet in his celebrated career as a filmmaker, he’s become one of the most respected figures in animation in the world.

Miyazaki is one of the few directors working in feature animation with an immediately recognizable visual style. His swooping aerial shots suggest a child’s dream of soaring through the air; he contrasts these visual and emotional flights with moments of quiet intimacy that heighten the reality of his fantasies.

“I don’t know of any artist more admired and respected within the animation industry than Miyazaki, as both a storyteller and a filmmaker,” said Hendel Butoy, who directed two sequences of Disney’s upcoming “Fantasia 2000.” “After screenings of his work, I always hear animators saying, ‘Why can’t we make a film like that?’ ”

And Eric Goldberg, who animated the Genie in “Aladdin” and co-directed “Pocahontas,” commented, “Miyazaki is a master filmmaker, completely in control of all the elements that make an animated film great. That he does so with such visual grace, economy and passion for the joys and fears of childhood is constantly astonishing.” Yet as Miramax prepares to release the English-language version of Miyazaki’s best-known work, Princess Mononoke, Friday in Los Angeles, the director said he’s frankly puzzled by the acclaim for his work.

“I’m completely baffled by the popularity of my work in America,” Miyazaki said with a shrug during a recent interview in Los Angeles. “I think it must prove that for all our superficial differences, we humans have a great deal in common.”

Although he speaks through an interpreter, he comes across as a genial, unpretentious man with a mischievous sense of humor. His statements are punctuated with sighs and laughs that require no translation.

The phenomenal ride of “Mononoke” in Japan–it grossed more than $150 million, won best picture at the 1998 Japanese film awards and drew record ratings when it aired on Japanese television earlier this year–perplexes Miyazaki, who noted: “I’m more bewildered by its success than anyone else.”

Born in Tokyo in 1941, Miyazaki became interested in animation after seeing early Japanese and Russian animation features. After studying political science and economics, Miyazaki turned his back on a conventional business career to become a manga (comic book) artist and animator.

He worked his way up through the studio ranks and made his feature directing debut in 1979 with Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro. Miyazaki breathed new life into Lupin, a James Bond parody figure created by manga artist Monkey Punch years earlier. He followed Lupin with Nausica of the Valley of the Wind (1984), an ecological fable based on his popular manga series. In 1985, Miyazaki and his friend, director Isao Takahata founded Studio Ghibli, where he has worked since.

At Ghibli, Miyazaki established himself as one of the world’s foremost directors of films for children with the rollicking adventure Castle in the Sky (1986) and My Neighbor Totoro (1988), a charming environmental tale. Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), an engaging story about an adolescent witch’s coming of age, ushered in a series of box-office hits for Miyazaki. (The English-language version of Kiki’s Delivery Service was released last year by Buena Vista Home Video.)

Porco Rosso (The Crimson Pig, 1992), a bittersweet romance about a dashing pilot in the 1930s who has somehow been turned into a pig, was an even bigger hit–to Miyazaki’s surprise. “I’m very troubled about Porco Rosso, because even though I said I was making a film for children, I was actually making it for middle-aged people,” he confessed. “Initially, it was supposed to be a 45-minute film for tired businessmen to watch on long airplane flights. I have only myself to blame for turning it into a full-length movie aimed at a middle-aged audience. Why kids love it is a mystery to me.”

Miyazaki set his next film, Princess Mononoke, in the Muromachi period (1392-1573), a time of unrest in Japanese history when women enjoyed greater freedom than they would under the later Shogunate. A vast, ecologically themed epic, it has little in common with the upbeat musicals and fairy tale stories Americans associate with animation. In contrast to the clumsy comic heroes in American features, the main character Ashitaka is a dignified, taciturn prince of a tiny village in northern Japan.

When a hideous monster with writhing tentacles attacks the village, Ashitaka kills it, but he is horribly scarred in the battle. The village wise woman explains the monster was a boar god, driven to madness and hatred by the pain of a wound from an iron bullet. Ashitaka sets out on his antelope steed to find the source of the bullet–and heal the conflict that caused the boar god’s madness–before his wound kills him.

“Ashitaka is a young man who doesn’t speak, which made him a challenge to animate,” Miyazaki said. “He shrouds many things within and below his silence; he does not speak of how deeply painful that scar is. The scar is also an entirely unfair curse, like the children today who are born infected with HIV.”

As he nears the source of the iron bullet, Ashitaka meets the title character, San, a feral girl Miyazaki modeled after prehistoric clay figures. Raised by the wolf god Moro to hate humans, San lives in an ancient forest ruled by the Deer God, who oversees the never-ending cycle of life and death.

Ashitaka is drawn into the conflict between San and Lady Eboshi, the ruler of a small town of iron workers who are cutting down the forest to fuel their furnaces. When he visits Iron Town, Ashitaka learns the bulk of the work is done by lepers and former prostitutes whose contracts were bought by Eboshi. Complicating the struggle is Jiko, a corrupt priest who wants to kill the Deer God.

“We have plenty of guys in Japan like Jiko, but Eboshi is different,” Miyazaki said. “She says nothing about her own painful past. I think both her mercy and her cruelty know no bounds. Her redemption of the prostitutes’ contracts is her expression of rebellion against a world where people are bought and sold like cattle. She takes great risks to make a stand against that system. It’s her way of challenging both the world and her fate.”

In contrast to the sneering Clayton in “Tarzan” or the brutal Shan Yu in “Mulan,” Eboshi is not a straightforward villain. Like the Japanese people after World War II, the workers in Iron Town are trying to survive in a troubled world; they don’t mean to destroy their environment. Even Jiko is just a small-time operator trying to get ahead.

“If you portray someone who’s evil, then you off him, what’s the point?” Miyazaki asked. “It’s easy to create a villain who’s a maniacal real estate developer, then kill him and have a happy ending. But what if a really good person becomes a real estate developer?”

(In the new English-language version of “Mononoke,” Billy Bob Thorton voices the role of Jiko; Billy Crudup is Ashitaka; Minnie Driver is Eboshi; and Claire Danes is San. The film opens Friday in L.A. and New York, and nationwide Nov. 5.)

The problems posed by rampant development, consumerism and other ecological issues figure prominently in Miyazaki’s work. “I’ve never wanted to make ‘message’ movies, but you can’t make a movie without some kind of theme, that’s a given,” he said.

Miyazaki is famous for juxtaposing visually and emotionally intense scenes with quiet images of clouds, streams and forests. When rain begins to fall, he lingers on a stone that darkens as it absorbs water. Time, budgets and the popularity of MTV-style cutting prevent American animation directors from giving audiences the moments of stillness that enrich Miyazaki’s films.

Glen Keane, who animated the title characters in “Aladdin,” “Pocahontas” and “Tarzan,” recalled, “The biggest impact Miyazaki’s work had on me was seeing how he had the courage to let simple things entertain us. A situation doesn’t always require a big explosion or a crazy gag. It can be something as simple as the way the wind moves flowers or the sound of a bee buzzing around a girl as she watches the clouds drift overhead. It encouraged me to find atmospheric moments in our films to animate, beginning with the eagle sequence in ‘Rescuers Down Under.’ ”

Disney story artist Joe Grant, whose career stretches from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” to “Tarzan,” added, “I enjoy dreaming along with him: He’s the original dream merchant. . . . It’s not a regular cartoon, but a work of art that moves; its pacing is beautiful and symphonic in its rhythms.”

For “Princess Mononoke,” which cost less than $20 million to produce, Miyazaki wrote the story, designed the major characters, drew storyboards and corrected more than half the animation drawings. As it neared completion, rumors circulated that “Mononoke” might be his last film because he was losing his eyesight. Although years of eyestrain have taken their toll, Miyazaki is at work on a new feature–although in a slightly reduced capacity.

“My eyes keep getting worse. On my next film, I have no choice but to be much less involved with the drawing than I have been,” he lamented. “It’s a question of whether or not the staff will accept my somewhat altered role as a director. I can see fine, but when I’m doing animation, I have to really see.”

In recent years, American animators have sought to infuse a personal vision comparable to Miyazaki’s into their films, a trend that can be seen clearly in Disney’s “Mulan” and Warner Bros.’ “The Iron Giant.” When asked about his influence on other filmmakers, Miyazaki said, “My own work has been influenced by so many different factors and films: All artists take their place in the continuing cycle of influencing and being influenced.

“In some ways, the history of art represents a great relay race, with each runner transforming the baton as he carries it. At some point, I’ll be ready to hand the baton on to the next generation–if they wish to receive it.”