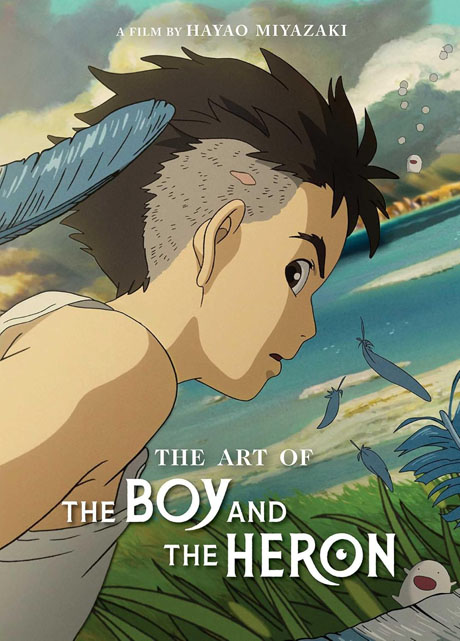

“The Art of The Boy and the Heron” opens with director Hayao Miyazaki’s self-deprecating Project Memo: “Isn’t it proof that you are aging when you imagine you’re still capable, but in fact you have memory loss due to senility? I would say yes.”

Audiences who saw the Oscar-winning film would say “no.”

The Japanese title of The Boy and the Heron, Kimitachi-wa Dō Ikiru-ka? (“How Do You Live?”) is taken from Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 juvenile novel (available in English from Little, Brown). In the book, 15-year-old Jun’ichi and his uncle discuss cowardice, courage, atonement and other moral issues. Jun’ichi gains an understanding of his shared humanity, an understanding that will help him grow into an honorable man.

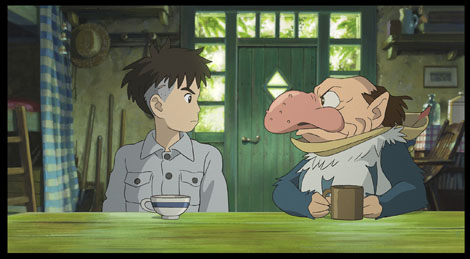

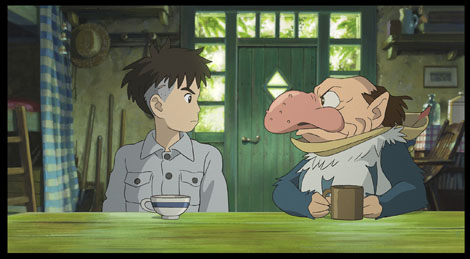

In the film, Mahito is tested in a grand journey that recalls Miyazaki’s earlier adventure-fantasies, from Castle in the Sky to Howl’s Moving Castle. Mahito confronts his fears and weaknesses, not in discussions, but in a dramatic quest. He emerges a stronger but kinder boy, who will also grow into an honorable man.

In his Film Proposal, Miyazaki explains, “The question is how you yourself live and by what means we objectively face each other. During the crises in human life, we must look squarely at things we don’t want to see and the things we don’t want divulged, and then leap past them. In this film, we do not seek an enjoyable, heartwarming touch. We must depict the courage it takes to withstand evil, demons and a world soaked in blood.” It’s hard to imagine an American director presenting a project to the staff in such grim terms.

As Miyazaki developed the story, he incorporated autobiographical elements. His family, like Mahito’s, manufactured airplane parts during World War II. Like Mahito, he was evacuated to the countryside during the Allied firebombing of Japan. Much of the film takes place in Tochigi region, where he stayed.

In another memo, Miyazaki said he didn’t want to produce a memoir, although: “This world was created almost entirely from my memories. I did in fact live for a time in a summer house that was large in its own way…the father here, Shoichi, is the spitting image of my own father.” He goes on to explain that he wants to discover how persuasively “…we can depict our protagonist slipping out of this trap, and how we can make it seem like there is value in living in this world after that escape. I believe this is our theme—no, our task.”

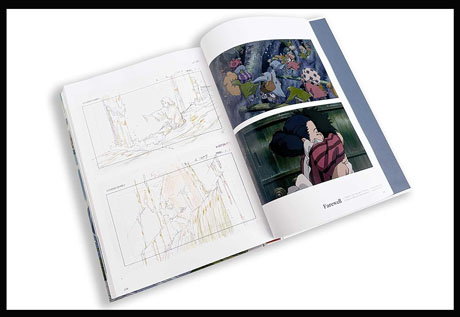

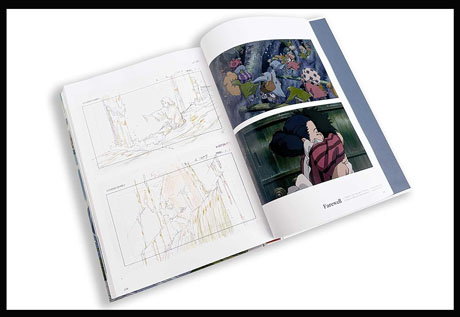

The amount of artwork Miyazaki produced for The Boy and the Heron is staggering. In addition to writing the film, he storyboarded it. There was no crew offering alternate visions of how to depict the action, as there would have been in an American production. The storyboards for The Boy and the Heron have been published separately: In them, Miyazaki shows not only camera moves and major actions, but the characters’ gestures and expressions. He essentially directed the entire movie on paper before the first scene was animated.

Miyazaki also drew hundreds of “image boards,” pencil and watercolor drawings that would be called inspirational or pre-production art in America, plus early versions of layouts, backgrounds and character designs. Although he was well into his 70’s when he began the project, his drawings have the vitality of the work of an artist half his age. Character designer Takeshi Honda reworked Miyazaki’s watercolor sketches into regular model sheets. Using a variety of media, the background artists built the world Miyazaki imagined, stroke by stroke.

Obviously, this method puts an enormous burden on the director, but the resulting film presents an individual vision unlike the communal productions of American studios. The most interesting younger Japanese directors (Makoto Shinkai, Mamoru Hosoda) also employ this method. While some American animation directors have a recognizable style, they are not auteurs in the same sense. The huge crews of American studio CG features preclude this kind of personal filmmaking.

This approach also requires the artists to commit to the director’s vision. Art director Yoji Takashige recalls, “Miyazaki told me he wanted me to paint a green never seen before, something totally different from anything we’d done before. So I started with tests for that…The key is to imagine the color inside the director’s head rather than thinking in words about what he wants to depict.”

The Boy and the Heron took almost seven years to complete, partially due to COVID restrictions. As the production stretched on, the artists sometimes doubted their work and the project. Takashige confesses after the initial screening of the finished film he was unsure about the story, but adds, “I think there’s something in Miyazaki’s film that soaks into that thirsty part of your heart.”

Although the film was made using a combination of techniques, it looks and feels hand drawn: a welcome reminder that animated features can be made in styles other than hyper-realistic 3D CG. But the most valuable lesson “The Art of the Boy and the Heron” offers aspiring writers and directors is the dub script at end of book. Although feature has a running time of 124 minutes, there are fewer than 20 pages of dialogue. Miyazaki understands the power of silence better than any director working today. His films remind us that animation is a visual art from.

Will The Boy and the Heron be Miyazaki’s last feature? Charles Dickens had a stroke while writing “The Mystery of Edwin Drood,” the pen in his hand leaving a line down the page. No artist would want to go any other way.

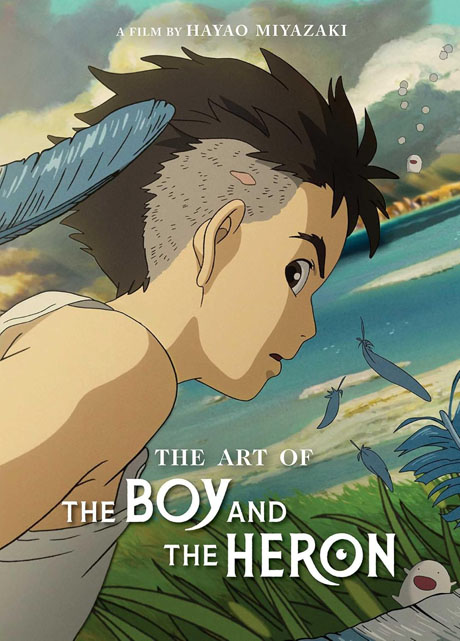

The Art of the Boy and the Heron

Jocelyn Allen , translator

Viz: $40.00; 320 pages; hardcover